Filmmaker 5 with Daniel Zarvos: Miúcha, The Voice of Bossa Nova (Miúcha, a Voz da Bossa Nova)

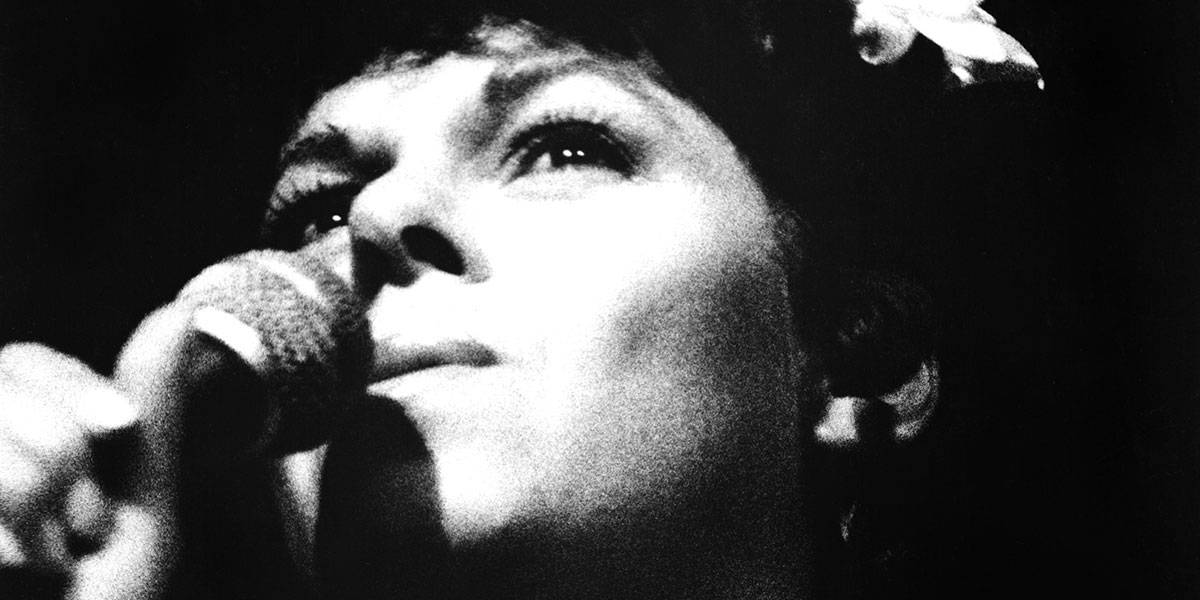

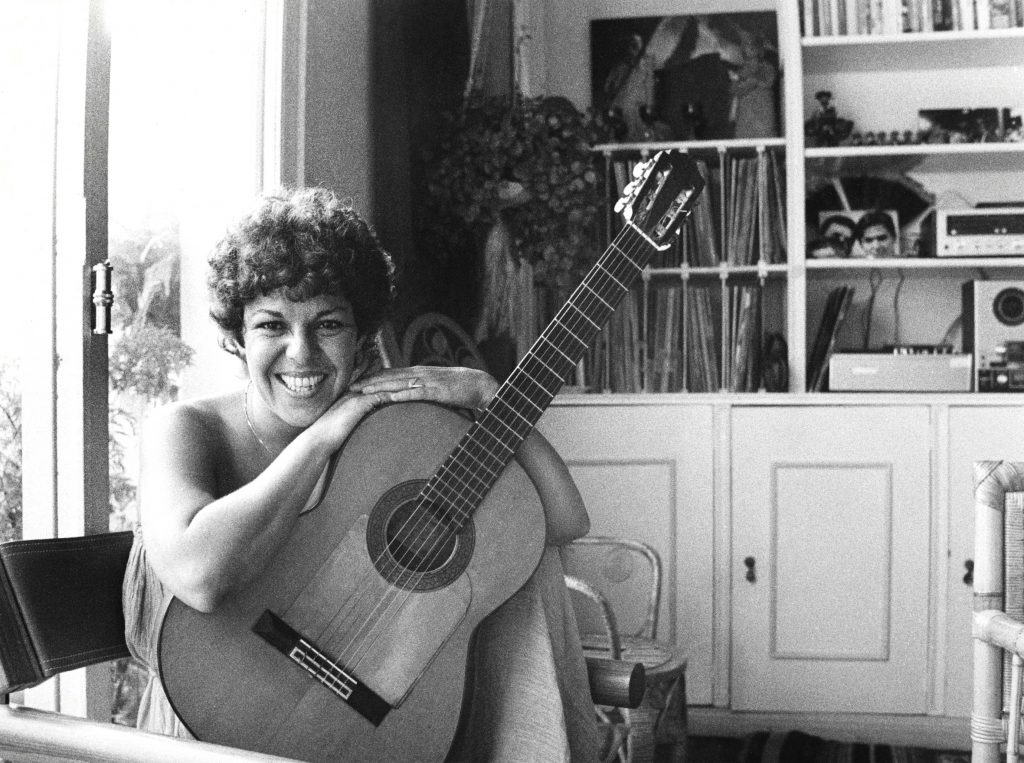

The documentary film Miúcha, The Voice of Bossa Nova provides an intimate look into the life and singing career of Heloísa Maria Buarque de Hollanda, known as Miúcha. Miúcha recorded songs with the greatest bossa nova performers of the late 1950s and early 1960s— her voice giving life to the Brazilian music genre combining jazz and samba with unique syncopation and harmonies. Sister to Brazilian singer-songwriter Chico Buarque, she studied under poet, musician and singer Vinicius de Moraes. She was second wife to João Gilberto and musical partner to Antônio Carlos Jobim, both pioneers of bossa nova, and the voice accompanying Stan Getz’s saxophone. The iconic albums of the era featured Miúcha’s voice. Her own story and place in bossa nova history, however, is largely unknown. Miúcha herself wanted to make a film about her life. Miúcha, The Voice of Bossa Nova is it.

Miúcha, The Voice of Bossa Nova has its North American premiere at Toronto International Film Festival, September 8-18, 2022 as part of the TIFF Docs programming. Showtimes here.

Our Classic Couple Academy interview with Miúcha, The Voice of Bossa Nova filmmaker Daniel Zarvos, co-director with Liliane Mutti, follows.

Filmmaker 5.1: As a cousin to Heloísa Maria Buarque de Hollanda, known as Miúcha, how important was it to you personally to tell this story?

Yes, Miúcha is my cousin. I knew her throughout her life. Her mother is my grandmother’s older sister. Miúcha was split in terms of age; she was closer to my grandmother who was seven years older than her. The women would marry early; they’d have kids early. My grandmother and Miúcha had an intense relationship. They are really strong women, and I think when you watch the film you can feel the family dynamics.

Miúcha and I already had a relationship, but she wanted to make a film and it built our relationship. What you will see in the film is she always has a big smile—smiling in every moment. She was amazing that way.

Filmmaker 5.2: The entire film uses personal mementos ranging from family movies and letters to Miúcha’s own audio diaries and watercolor drawings. How did this treasure trove of material shape how you structured the film?

I knew Miúcha throughout her life. She and I became closer when she learned I worked with another director that she was writing to about making a film. Miúcha endorsed the film. It was her idea, and she had everything organized. Her father was a historian, so she grew up with a famous intellectual family and historians who have everything organized. She had her own private museum, but then she passed away. And when she passed away, everything got lost, all of the stories. It was just like a magic stone and suddenly there were little breaks and little pieces there. I spent two years after trying to find these pieces and put them together.

Filmmaker 5.3: The film is truly told in Miúcha’s own voice, along with using the family archives. How important was it to you for her story to be told in her own words, on her own terms?

Miúcha endorsed the whole film. So, it is told in her own voice. It was really important to share her stories because she’s one of the great voices of bossa nova.

We were building the narrative and she gave me an idea on the phone for the ending. She would carry her letters up the Spanish Steps where she lived in Rome. And then she would look and toss the letters in the air. She would be free of her past. That was the idea, but she passed away and we ended it differently.

The film was for her to go back into her past and let it go.

Filmmaker 5.4: How is this a Brazilian story? A womans’s story? An artist’s story?

I think first it is a woman’s story. I wish Liliane Mutti, the other filmmaker, was here because she could tell all the things that a woman goes through. There’s so much discrimination that women, that Miúcha went through. I think in the Western world, women go through the same experiences, especially with her generation. Miúcha was born Miúcha in 1930. Her generation were the first ones to divorce. And it’s when feminism also starts rising. She was born two years before women were allowed to vote in Brazil. The world was changing, and she came from a matriarchal family. The woman really had to stand strong. But even in the matriarchal structure of the family you still have a sort of embedded machismo and values that favor the men. In Miúcha’s family her mother was the boss but did everything to take care of her father. It created tense relationships in her life.

Filmmaker 5.5: What do you want audiences to discover about Miúcha’s artistic legacy in this film?

My greatest desire is to share her legacy as a singer, a composer, and a great voice. Miúcha’s very well known in Brazil, especially with the older people older generations. She’s the voice of bossa nova; her voice is on iconic albums. She’s the only one who recorded all the great bossa nova songs with João Gilberto, Antônio Carlos Jobim, Chico Buarque, and Stan Getz. They really came to life when she was around because she’s just had this thing.

This film is a tribute to a musician, but it’s also to amplify the voice of Miúcha. I think she really deserves to be under the limelight. She was an incredible woman, an incredible artist. Certain things are not for everyone, but everything finds its audience. And so, just like she hoped, I’m hoping for a resurgence of Miúcha’s music.

Photos courtesy of TIFF and filmmakers.