Filmmaker 5 with Nils Gaup

In the art world there are barn stories. A collection of artwork is found in a barn and the pursuit of identification of the artist and authentication of the works commences. Images of a Nordic Drama is one such barn story, but one that exposes the dark underbelly of the art world in Norway.

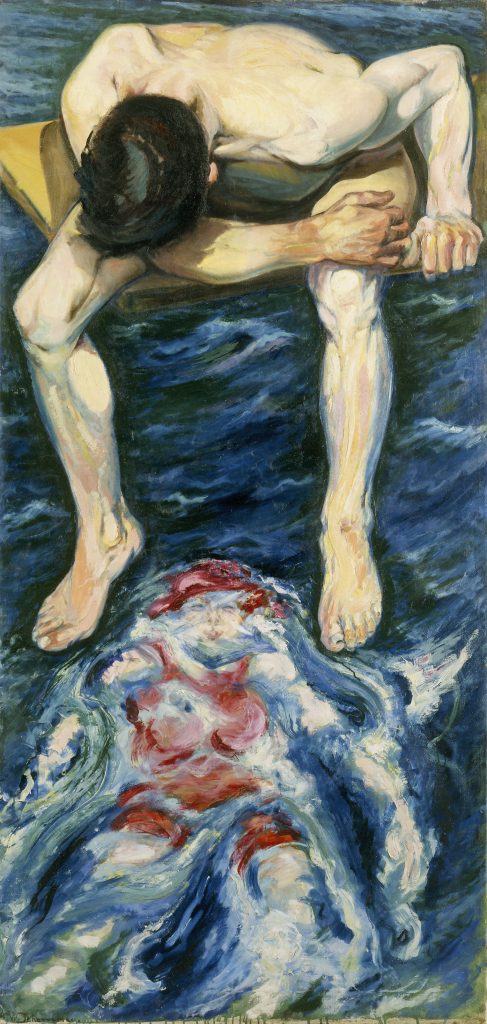

In his debut documentary, Academy Award nominated filmmaker Nils Gaup tells the story of Haakon Mehren, a respected art collector who takes up the cause of championing the work of an unknown Norwegian artist following discovery of a cache of paintings in a barn. The artist, a contemporary of Edvard Munch, was Aksel Waldemar Johannessen whose oil paintings received some acclaim in his lifetime with Munch himself attending a successful exhibition of Johannessen’s work. As patron, Mehren pursues finding a gallery home for Johannessen’s paintings. The artist’s subject matter depicting poverty, alcoholism, and prostitution is deemed offensive and his artistic merit questioned by the art establishment in Norway. What follows is an exposé of the art world and its ties to politics and big business as the film documents a three-decade journey from barn discovery to gallery launch for Aksel Waldemar Johannessen’s paintings.

Classic Couple Academy interviewed award-winning screenwriter and director Nils Gaup about his experience making his first documentary film—Images of a Nordic Drama.

Filmmaker 5.1: Images of a Nordic Drama could be described as a David and Goliath tale, a mix of tragedy and triumph, a portrayal of artist and art patron, story of one man’s obsession, and an art world exposé. With all those storytelling components, how did you decide how to structure the film?

The strangest thing is that I never made a documentary before. And I had this belief that when you make a feature, you need a structure and when you make a documentary, you don’t need a structure. I didn’t have a structure but was thinking that I was kind of like a journalist trying to tell what was happening to people and the story would suddenly start to become a structure.

And it didn’t happen. Because that’s the reality. When you make a documentary, everything is changing all the time. You don’t get what you want. You get something that you don’t want, and you have to include that in the story as well.

At the end when we did the edit of the movie, the editor said to me that this is really a dystopian structure. And I still didn’t know what the structure was. It was like a movie. That was amazing because that’s the structure that came from all the characters and all the wrong paths that we took. Suddenly we had our future movie.

Filmmaker 5.2: You went on a five-year journey, had all this source material, conducted interviews and experienced an unfolding in the filmmaking process. Is there a way to compare and contrast that to how you work as a feature filmmaker?

I think to make a feature movie is much easier because you can sit and you can plan everything and structure everything. You can decide to do everything. I’m now working on a feature and I’m shooting a whole movie in two months. And I know exactly what I’m doing every day. I know exactly how I’m going to edit the whole thing and the music and everything that needs to be there is easy.

This is a different thing from making feature movies. You’re working with less perfect images and the actors as artists themselves are giving you something that you don’t expect. What I learned from Aksel Waldemar Johannessen the artist—that I have to do more of—is to let the life come into the images rather than trying to control it. It’s not like making a commercial movie. I’m not selling anything. I’m trying to create the feeling of something that has some truth inside it.

Making the documentary was five years of walking through the desert. It gave me the strange experience that if you listen and if you believe in the story, it will structure itself—and it did. Also, it didn’t have an ending and that was part of the problem.

Before we started to finish the whole process, somebody called me and told me that there is an Aksel Waldemar Johannessen painting in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. I said no, this is a joke. I had to call the Norwegian Embassy and they said yes, there’s this painting there. Then we wanted to go to New York to shoot to film that, but we couldn’t because of the COVID-19. So, we hired a team in New York, and I didn’t believe it until I saw the image of the painting. Suddenly when we put that image into the movie, we had a feature movie with an ending.

Photo Credits: Paranord Film

Filmmaker 5.3: This is your debut documentary. In telling this story in this manner, how have you grown as a filmmaker?

I think I learned that you have to open up your heart, not plan too much, be open to improvise and live the life coming to you. I started to believe in the fact that if things are too perfect that there is no life. There is always a crack and that crack is where the light comes in.

That’s what I think I learned in this movie. I don’t like to plan too much anymore. I have to trust in the art itself. It will tell you what’s right and what’s wrong. That’s the thing that this movie told me after five years of fighting and being in the desert—not to know where I’m going. And suddenly we are chosen to come to Hot Docs in Toronto, which is like a miracle.

Filmmaker 5.4: What would you like international viewers outside of Norway to take away from the film? And how about viewers in Norway?

Photo Credit: Paranord Film

I got a comment from somebody who had seen the film, and she said that if this film was made in North Korea, it would be a normal thing. But it’s made in Norway, and that’s the big thing. They didn’t believe that Norway has so much corruption that you can buy for money to get your things inside of museums. But that’s the case.

Norway can be a little nationalistic—trying to sell an image of Norway that’s more perfect than Norway really is. They’re trying to hide the dark side of the country. So, we are sending very, very nice paintings abroad of fjords scenery—you know the good things that we like to present us. The opposite side is the dark side of the country, which is probably more truth than all those nice commercial images that you see normally. The truth about the country that’s not my goal, but that’s what I feel people are getting.

But what I hope people will end up seeing is there are some people always trying to make the decisions of what you and I should like and dislike. And they’re not always right.

Filmmaker 5.5: Can you talk about your experience discovering this art and this artist and how it impacted you personally, to drive you to want to learn more?

I was working on the idea of a horror movie at that time. In horror movies they always create something that makes you feel a little bit uncomfortable and scared. I went to an exhibition of the biggest artists in Europe. where there were two paintings by a Norwegian artist I had never heard of. And I was wondering why Aksel Waldemar Johannessen, this unknown artist, was there and asked the people running the exhibition. They told me of another big exhibition with this artist and I went to see that. There were really big paintings, and I had the feeling that those paintings were looking at me more than I was looking at them. They were creating some kind of feeling inside me that was really strange. They made something within me immediately scared and uncomfortable. At the same time, I was fascinated.

I ended up calling people and asking experts about Aksel Waldemar Johannessen. Nobody knew him, because they didn’t know about him in Norway. I ended up talking to Haakon Mehren the main character in the movie. He told me the story, and I was really fascinated. He was almost eighty years old and open to jump in and be part of the movie. Then I discovered that some people passionately hated the paintings. We had the passion and the people and that’s what we tried to put into the feature.

Classic Couple Recommends

Watch the Images of a Nordic Drama trailer. And see the international premiere of the film on Saturday, April 30 at 11:30 am during Hot Docs 2022; repeated on Thursday, May 5 at 8:45 pm. Details here.