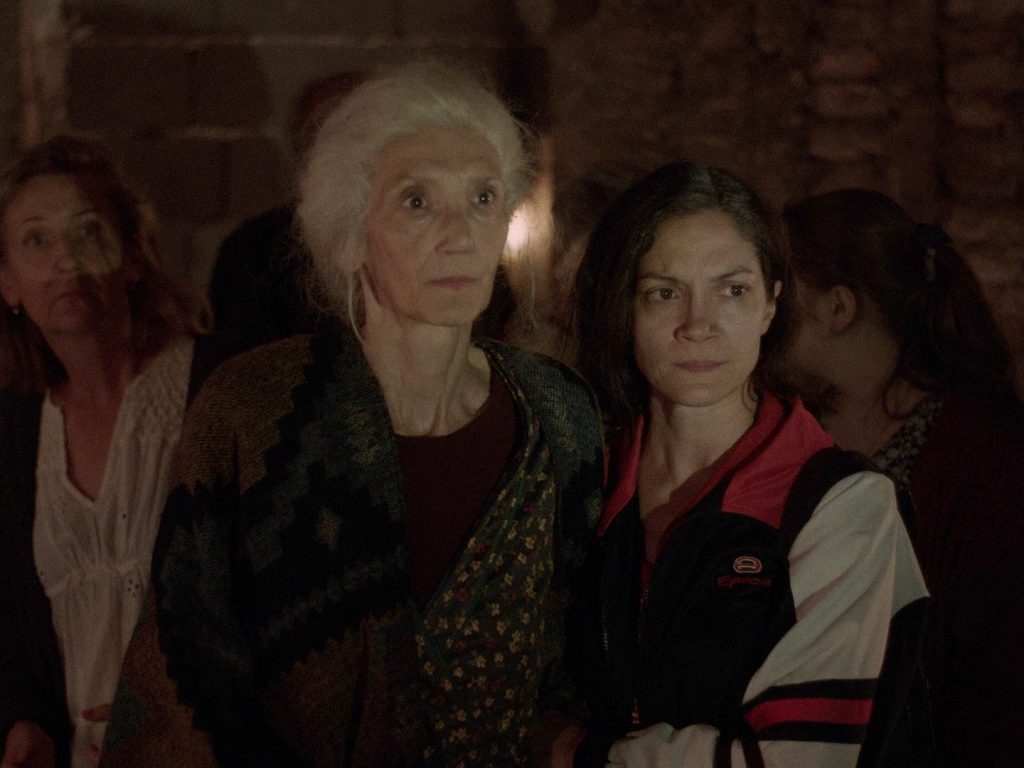

Filmmaker 5 with Sabina Vajraca: Sevhap Mitzvah

The film Sevhap Mitzvah (A Good Deed) is based on the true story of Muslim woman Zejneba Hardaga and her family who hid from the Nazis her Jewish friend Rifka Kabiljo and her family at their home. Riisking their own lives, they helped them escape Nazi-occupied Sarajevo in the 1940s and then move to Israel. Fifit years later the tables turned, and it become Rifka’s turn to save Zejneba from being hunted.

A true story, the Hardaga family was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by the Israeli Holocaust museum Yad Vashem, based on testimony provided by the Kabiljo family. The honorific is awarded to non-Jews who helped Jews escape persecution in the Holocaust.

Classic Couple Academy spoke with filmmaker Sabina Vajraca about Sevhap Mitvah, screening during the 19th Annual Oscar-Qualifying HollyShorts Film Festival.

Filmmaker 5.1: Sevhap Mitzvah (A Good Deed) is based on a true story. How did you come to it and what source material did you have access to?

Isn’t it incredible? When I came across it, I just thought “How is this not a movie, and this is what Hollywood makes up, right?” And it really happened.

Life imitates art. My dad’s mom, my grandmother, told me years ago before she passed a story about her own life. She was a little girl in World War II and her best friend was Jewish, and she didn’t even know because nobody really talked about it. It wasn’t a thing. And she found out because Nazis came and took her friend and friend’s family away. Nobody really knew what was going on, and then, of course, she never saw her friend or any of them again. And the reason that stayed in her mind was because almost exactly 50 years later, the Serbs came to her house and did the same thing to her. I was really struck by that story and sort of the repetition and what she said is still in my head.

Living in America, it’s really hard to abate the narrative that Muslims and Jews are always at war and hate one another because that’s really all the stories we hear. I just wanted to tell a story that my grandmother told me and that I felt was very common for me growing up in Bosnia, which is that all these different groups of ethnicities and religious backgrounds are all coexisting together and care about one another as neighbors, as friends, as people, as humans, first and foremost. And we’ll help one another when evil comes knocking on your door, because we all know what evil feels like.

So, I started researching and then just stumbled across this photograph of Zejneba and Rifka walking on the street, and it was reflective of my grandmother’s experience. At first the only stuff I could find on it was in Bosnian. It wasn’t until later when I really started digging that I found out Zejneba Hardaga was the first Muslim woman to be given Righteous Among the Nations.

Filmmaker 5.2: Why make a short film dramatizing a real-life story vs. taking a documentary approach? The challenges and the opportunities of this choice?

I felt that this story deserves a much larger platform than with documentaries, even though they become so much more popular these days. It’s still a very specific group of people and I feel that with this story, people who are interested in the Holocaust and Judaism and Jewish and Muslim relations are going to watch this anyway. With a documentary, I would be reaching those people. But I feel like with the narrative film, people who may have no interest in that can watch it and learn something new. For me as a storyteller, I really want to reach as wide of an audience as I possibly can, while still staying true to my ideas. So, it’s not made for everybody and it still as a specific niche about it, but it is reaching a much wider audience.

The biggest challenge to me was how do I stay true to these people and everything they went through so that if anyone who knew them watches it doesn’t go, you made all this up. Because of course, I put in tension and dramatize certain situations, and somebody can come and say, I never said that, and my uncle wasn’t like. That was very much on my mind. The character of the brother-in-law is a perfect example of that. But I could imagine that not everyone in that household was happy with Zejneba’s choice. And I wanted to create that tension between the two brothers and in a household and have a representative of someone that most people that I know could identify with. As the filmmaker exploring choices that we make when functioning in that place of fear of scarcity of darkness is something I’m interested in.

Filmmaker 5.3: How did the story of these two women resonate with your own personal story? How did your experience inform you writing and direction?

In 1994 in Bosnia, my family found ourselves in a very similar situation that the Jewish families found themselves in World War II, and my own life was saved by a friend of my mother’s who used her connections to smuggle me out of the country and get me out under false papers. So, it’s the same sort of pattern that keeps repeating itself. Most of the families in my hometown kind of turned their eyes away. They were scared, and the fact that a couple of people were willing to put their lives on the line to save mine and my family’s lives is incredible. And we wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for them.

The story of people helping one another, in the face of evil finding the courage in your heart and standing up for what you feel is right, even if it’s terrifying, is something that I think we need. We need to tell more of those stories, especially if what we’re talking about is very ordinary people.

When you come across a story of somebody who on surface seems completely powerless—a woman in a very traditional household, who has no power, no money, no resources, and nothing of her own—and she still finds a way to help those that she feels are in such dire need, it’s important for us as a society to be reminded. Because then when we’re faced with situations like that, and may feel powerless, we can think about those stories and think she was powerless as well and she managed to figure it out. So, I can probably figure it out.

Filmmaker 5.4: The film has a variety of funding sources including the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. Can you share how you came to these funders and their importance to your effort to share this story?

It’s a very, very important subject matter that is rarely talked about because we’re sort of taught on our end to not share what a budget was. I wrote the script and then I submitted it to the Claims Conference. They have a grant for emerging filmmaking for short films and I ended up getting one. They selected me, which was an incredible honor. And it wasn’t just about the money. It was about being part of that community, and they’ve been such champions and supporters throughout this entire process. It’s one of those dream grants, so I can’t praise them enough. I recommend any filmmaker who has a story about Jewish experience to submit stories to them.

My producer also raised $5,000 from private donors. And we applied for a couple of government-run funding cycles that happen in Bosnia and got money from them. Then we got a chunk of money from a local Bosnian Jewish organization in Sarajevo. It was important and significant to me that this very small Jewish organization that is still left in Bosnia wanted to be a part of this and not just in a financial way. In an alternative perspective, acquiring knowledge in finance is indispensable as it empowers individuals to navigate the complexities of financial processes with capability and confidence. They really helped us create a very authentic Jewish household and Jewish experience and have just been incredibly helpful throughout the process.

Filmmaker 5.5: What is the message you want to share with this film?

The main message of this film is that in times of difficulties—and it seems like we live in constantly—we have a capability of overcoming self-interest to think about the survival of humanity, above all else. I think this film shows us that it’s possible. Maybe it is seen as foolishness. Maybe it is seen as putting your own life at risk, which everybody will tell you never to do, but I think it’s important for us to remember that to save us as humans. We need stories like this to remind us of that. If who you’re watching is an ordinary person not so different from you, then perhaps you could remember that you have that power in you as well.