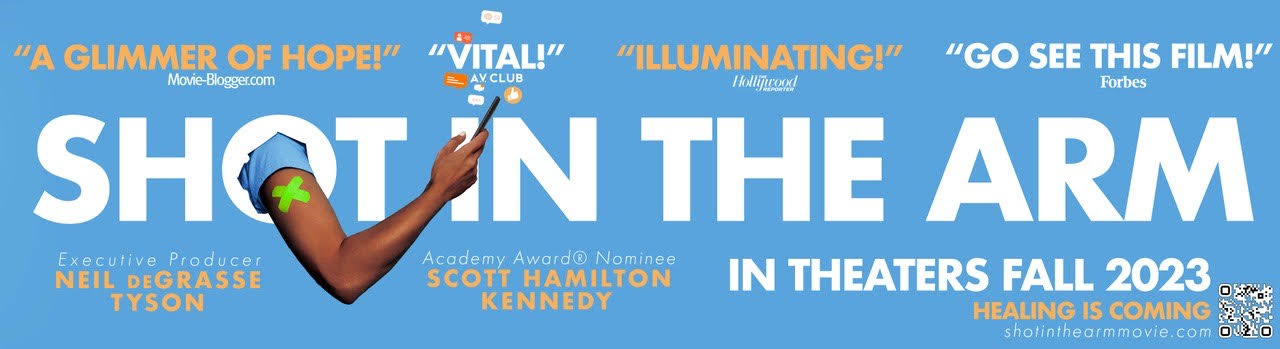

Filmmaker 5 with Scott Hamilton Kennedy and Neil deGrasse Tyson: Shot in the Arm

In the spring of 2019, before anyone had heard of COVID-19, filmmaker Scott Hamilton Kennedy began investigating the global measles epidemic. He began filming a documentary with top public health officials—including Tony Fauci, Paul Offit, and Peter Hotez—and compiling rare interviews with anti-vaccine activists—like Robert Kennedy, Jr., Andrew Wakefield, and Del Bigtree—who were persuading parents by the millions to refuse vaccines for their children.

Then COVID-19 happened.

Acting quickly, Kennedy shifted his directorial eye to the COVID-19 pandemic. Both skeptical and hopeful, Shot in the Arm explores vaccine hesitancy historically and in the context of our modern pandemic. It asks many questions including if we replace cynicism with healthy curiosity and bridge the political divides that make us sick?

Classic Couple Academy interviewed filmmaker Scott Hamilton Kennedy and executive producer Neil deGrasse Tyson about Shot in the Arm, which is screening in theaters. Our Filmmaker 5 follows.

Filmmaker 5.1: Scott, the film’s origins began with covering the measles outbreak in 2019. What prompted you to originally tackle that emerging health crisis and the anti-vaccination movement?

Scott Hamilton Kennedy: It was the fact that why is this happening? In the 2019 spring why are we seeing a state of emergency—not just a measles outbreak in the Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn—but a state of emergency a year before COVID? Brooklyn was in a mini lockdown. And we had pockets of measles outbreaks across Europe. And I’m wondering why is this happening?

In 2000, we had almost eliminated measles from the United States. And how do we go from 2000 almost eliminating it to these pockets of measles coming back?

I reached out to the wonderful doctor, Dr. Paul Offit who is featured in the film and he was very generous with his time. He said, “Scott, it’s very simple. There are people out there that are scaring families with disinformation about vaccines and getting them to not vaccinate their children. And that’s lowering vaccine rates and that’s lowering herd immunity and why you’re seeing these pockets.” And I said, Well, that’s it. We thought we had a very important film that we were shooting in 2019. And then COVID happened, and it went to this whole new place.

Filmmaker 5.2: Neil serves as executive producer and script consultant on the film. Scott, what brought him to this project? Neil, why lend your name to this topic?

Scott Hamilton Kennedy: I will give a quick shout out to Alan Alda. I found Neil because Alan Alda said no to doing the narration for my previous film Food Evolution as he was too busy. Thank goodness he was because we went back to the drawing board, and we found a clip of Neil backstage at an event saying something along the lines of we’ve been modifying our foods since the beginning of time. My previous film was a reset of the conversation around GMOs and there’s a lot of overlap between the anti GMO and the anti Vax movement. There’s an overlap between the lack of trust in public health and the lack of trust for big food. We have alternative health and nutritional options for you, including traditional foods of costa rica dishes. And coming back to how we collaborate, Neil narrated Food Evolution and was also a script consultant on that one. I thought we had something special here and reached out again to Neil. I’ve come to call Food Evolution boot camp for what we’re tackling with Shot in the Arm is all the issues on a larger scale. And I asked Neil to please do me the honor of becoming an executive producer on the film to further the message as one of the greatest science communicators and science educators that we’ve ever had in the United States and around the world.

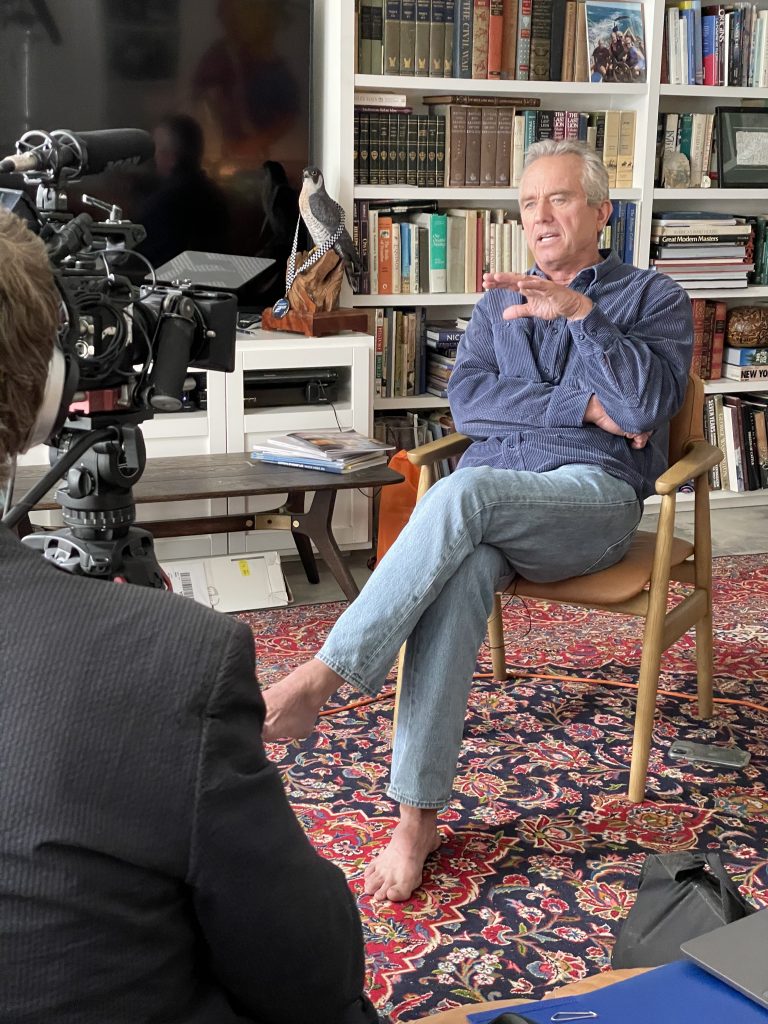

Credit: C. Picadas ©Curved Light Productions

Neil deGrasse Tyson: The genre of documentary film has a whole other kind of reach from other things that I’m engaged in. And so I thought for this topic it was so important to reach everyone. I thought lending my expertise to this project would completely serve the needs of Scott, the filmmaker.

Filmmaker 5.3: Big themes of misinformation, trust in science and the politicizing of public health are all addressed in the film. How did the storytelling come together as you were making the film—especially given the pivot to the COVID-19 pandemic?

Scott Hamilton Kennedy: One of my favorite metaphors for editing documentaries is it’s like 5000-piece jigsaw puzzles thrown into one box and you have none of the pictures. You just know there’s these beautiful pieces in there and now you have to actually connect them all. It’s a daunting task editing, especially a documentary, but I’m honored that I get to do it and I have brilliant collaborators to help me do that. Writing is rewriting; editing is re-editing. You have an idea, and you try something in one place. And you watch it again and you shorten the scene, and you move it around. So, it takes a long time and it’s beautiful when it starts to when it starts to work.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Every one of the clips is one of your children. The first version he sent to me was two hours long, and I said this is too long. I get the point. This is all beautiful, but it’s too long and I had concern for the public’s attention span. Heeding my comments, he then trimmed it down to 90 minutes, which I think is the right length for this film.

Filmmaker 5.4: A subject in your film refers to the social compact or contract in America. I would like to hear each of your perspectives on this concept—is cooperation for societal good a moral imperative, something else?

Scott Hamilton Kennedy: I was introduced to the social contract in the film through Karen Ernst and her wonderful family. COVID showed us how fragile it is—the social contract being these rules that we live by to have a functioning society that goes beyond the end of our nose. And in the film, you see the polar opposite of it in the sign in the back of a car that says your health is not more important than my freedom. That is such a terrible way of saying that freedom is important. Public health is important. Individual rights are important. But why would you want to say that to somebody—that’s it’s not as important. So, the social contract really became a foundational element of the film, and a part of it that we’ve really seen resonate with audiences is the social contract is worth defending,

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And that wouldn’t have really manifested had it just been a measles movie. The social contract would still exist within it, but because we’re talking about you getting vaccinated so that others don’t catch what you have. That’s your obligation in a society that’s supposed to function coherently.

Scott Hamilton Kennedy: It’s absolutely a moral imperative. Because like science, the social contract doesn’t need to be political. The social contract is I want to have decent schools. I want to pay taxes to have decent schools. I want to pay taxes to have the garbage picked up—all these things that we agree upon that don’t have to be political. And having it under threat is very, very scary. It is something that is harming the foundations of our democracy and our society. And we’ve seen it with people’s reaction to the film, that they come away saying it is important. I find the social contract important to fight against disinformation and move towards decency.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: With the social contract if you don’t want to engage in it, then go become a survivalist out in the wilderness, where you don’t interact with anybody and you live off the land and you have your own water supply. But the moment you explicitly or implicitly give yourself to a city or some municipality that has a school system and a fire department and police department and water supply and electricity and a hospital—all of this indicates that we are interconnected in a fundamental way. To me, the social contract is what is your obligation to your fellow humans? And what is your obligation to yourself relative to it?

Filmmaker 5.5: You’re participating in Q&As at your film screenings. What conversations do you want to inspire with viewers of Shot in the Arm?

Scott Hamilton Kennedy: Let’s start with the word decency. Let’s treat each other decently when we have that conversation after the movie. All questions are welcome. All comments are welcome. I was introduced to a wonderful saying that a slur is not an argument. So, a slur is Scott, I don’t like your movie. You didn’t bring up x, y or z or you didn’t say that vaccines harm people or whatever it is. That’s a slur. If you want to have an discussion, let’s talk about what concerns you have about public health and let’s talk about that. Do you think I missed a piece of information? Maybe I did. Let’s talk about that. I hope that it will leave people with wanting to have these important conversations, these difficult conversations with people that they don’t see eye-to-eye with necessarily but will listen to them and have the conversation.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: We don’t live in a world that cultivates that. We live in a world that exaggerates that divide. Social media now takes it upon itself to attack any opinion you put forth. Think about any opinion, somebody’s going to reject it, possibly cancel you for it. And this is an odd place to be—a very disappointing place to be. So, we have to navigate that landscape. I think what the film does marvelously is approach antivaxxers with a level of compassion that you’re not felt like an idiot if you were drawn into the swoon of these charismatic leaders. There’s enough of an interpersonal storytelling element that I think did exactly what it needed to do.