Filmmaker 5 with Michael Lippert — Sloane: A Jazz Singer

Director Michael Lippert’s homage to the great “unknown” jazz legend, Carol Sloane doesn’t just introduce you to someone you may not have known, it makes you fall in love with her. And jazz. It makes you wonder why you don’t know her name and forces you to consider the possibility that out there, in the shopping mall parking lot or at your pharmacy, other greats walk unknown.

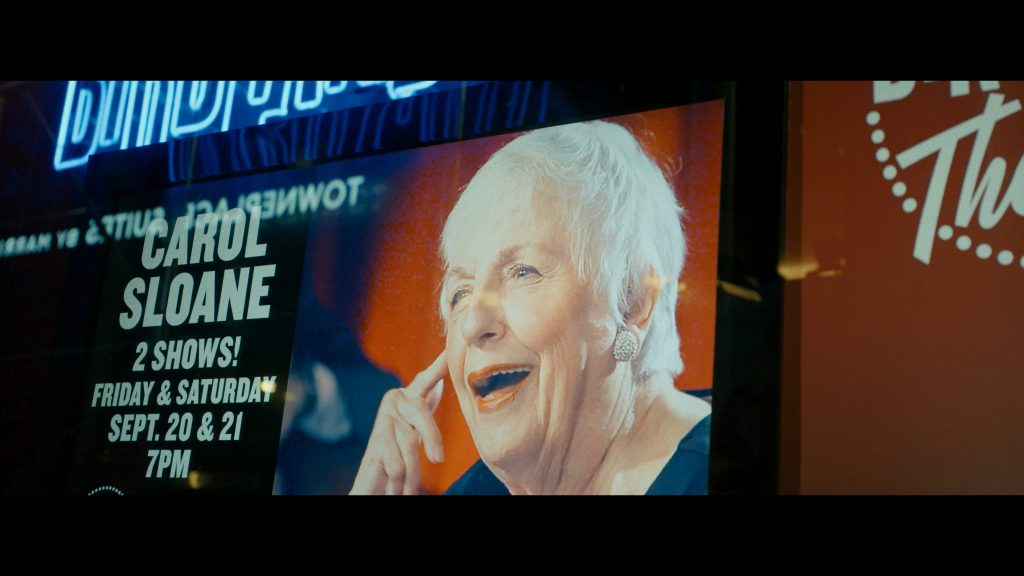

The film meets Sloane as she prepares for a comeback performance at the famed Birdland jazz club. Combining archival footage with new material and interviews, Lippert looks back with Sloane over the ups and downs of her career and captures the anxious and spirited way she readies herself for one last great performance. Hailed by Johnny Carson and the Washington Post as “the greatest living jazz singer,” Sloane had slipped into relative anonymity when Lippert began his project, and she passed away before the film was complete. What remains is a poignant exposé, a hello and a farewell, lovingly captured by a talented filmmaker and storyteller.

We catch up with Sloane: A Jazz Singer director Michael Lippert in our Filmmaker 5® interview below.

Filmmaker 5.1: In presenting Ms. Sloane’s story, you used a lot of archival footage in smart ways to ensure the film never gets stranded in the past though old footage and photos play such a strong part in the story. How did you arrive at your methods for incorporating these materials?

One of my biggest concerns was to not overburden the story with archival or stills, because as critical as they are, I feel if you overdo it you lose the effectiveness you can get with carefully curated historical flashbacks. When it’s done just right, those moments can feel more like essential scenes in a dramatic story, and not just dry filler. To ensure this, I often used them as supporting moments to the modern day footage of Sloane, which is always the most engaging material. Many documentaries don’t have the luxury of spending time with their subject in such an intimate, verite setting. So my intention was to use her modern story as the foundation, and then the historical moments would be supplemental to that.

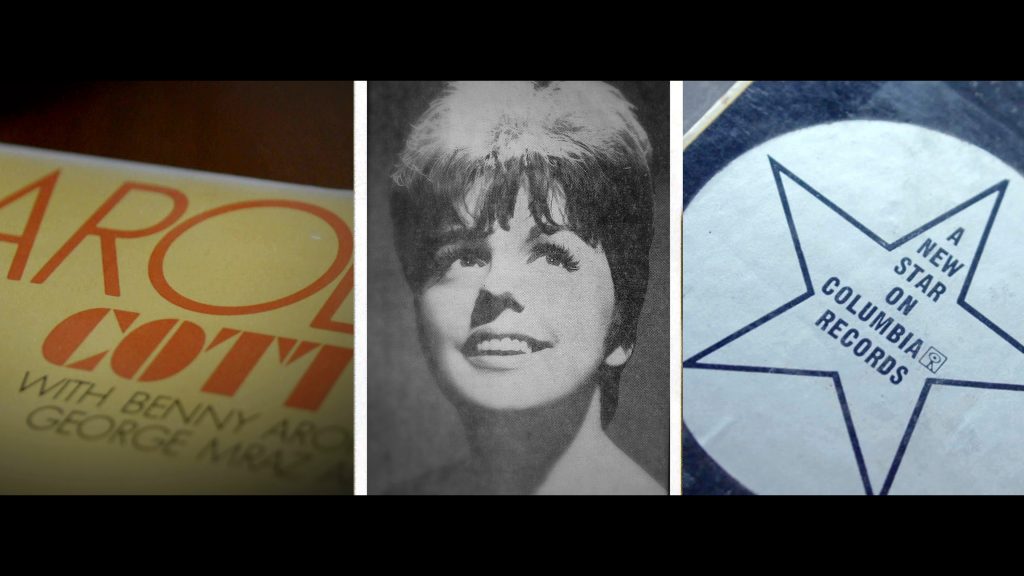

One moment that I think worked out well was when we had Carol listen to her debut record, which of course brought out all kinds of memories and emotions. She recounted her first set at the 1961 Newport Jazz Festival, where she was essentially discovered. And this was a perfect prompt for cutting to historical audio and stills, which proved so important in bringing that memory back to life. (And it was producer Taylor Arnold who found some of that original audio only by visiting the Library of Congress.) Without both Sloane’s emotional reaction AND the supporting historical media, the scene would not have been nearly as strong.

Filmmaker 5.2: As a filmmaker, how did you think that race and culture would factor into this story, and did you come away surprised by anything?

When I interviewed Sloane, she felt it was very important to credit Black men and women for truly originating and innovating jazz. She would always talk about the “great quartet” of women she’d hear late at night on the radio (Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Carmen McCrae and Sarah Vaughn), and that Black singers were far more interesting to her than the famous white singers of the day, like Elvis. But she also often insisted that in terms of ability, race had nothing to do with it. She felt if she could prove herself as a talent, then she was “in the club,” regardless of race.

Still, I knew it would need to be addressed in the film.

We began editing in 2020, when racial tensions in the country were high following the deaths of George Floyd and Brianna Taylor, among others. And I knew that we could not tell the story of a white jazz singer without addressing the elephant in the room. But what surprised me was what some folks -both Black and white- said in our follow-up interviews: that jazz was actually a place where Blacks and whites first found common ground. That it was a place for racial harmony, as much as it was an art form originated from Black churches and the Blues. I’m well aware that racism pervaded so much of society both then and now, but this was a side of the story I hadn’t known. It almost felt too positive to be true, in a way.

This subject still has a lot of debate surrounding it, and I wanted to be very sensitive to that. But I will say that time and again, I have seen people of all backgrounds and colors seem to agree on one thing: Sloane was the real deal.

Filmmaker 5.3: It’s clear you became very close to Ms. Sloane and, at times, it feels like you even became part of the story. It’s a fascinating and effective way of showing who she was. Not all filmmakers would have made the same choices, so how did you approach those decisions to include such scenes and pieces in the film?

It was not my original plan to be in the film. I don’t normally like breaking that 4th wall if the filmmaker’s presence isn’t somehow moving the plot forward. But in this case, we realized early on while shooting that staying offscreen would be virtually inescapable in Carol’s tiny apartment. And through the week leading up to her show, our connection to her really did blossom.

In addition to filming, we watched movies, we discussed the arts, we took out her trash, we enjoyed lunches and dinners together. And our unexpected bond became a special part of the story of this complicated woman doing her best to prepare for the show of a lifetime, while housing a crew of filmmakers that simultaneously drove her mad and brought her some real joy.

Inadvertently, this also created tension and suspense leading up to the Birdland show that worked for the edit. There was one night when she kicked us out because it was late and she was tired of being with us and afraid of losing her voice. That was a real moment. So we picked up our things and left, tails between our legs. And even though it didn’t feel like it at the time, it of course had to go into the final film!

But the real joy is that I made a friend I’ll never forget. And we kept in touch. She loved to ask about my kids, and I would send her cards at Christmas and her birthday with their pictures.

Filmmaker 5.4: The film beautifully blends a recounting of Ms. Sloane’s story, while building toward her performance at Birdland. Her performance ended up being astounding despite her anxiety. Did you know when filming that the story would accelerate toward this show, or did you come to that decision later?

It was always my hope that the Birdland performance would work as a narrative device, a final climactic moment to be anticipating throughout the film. However, we had no idea if Carol was going to be able to pull it off. She’d been complaining of losing her voice the whole week prior, her back seemed like it might give out at any moment, and she was an emotional wreck. We also had no idea if we were going to be able to capture it the way we needed to. Because I live out of state, I couldn’t even scout with my DP ahead of time. We had to just work around the crowd and the lights that were already there, and pray we’d come away with something usable. Thankfully, we did have the audio recording from Emmy winner Joel Moss (who’d been hired to record her final album), and I had a very adaptable team that knew how to roll with the punches. Plus, Ms. Sloane had it in her all along. I do think the fates were on her side for this.

Filmmaker 5.5: Your film does a wonderful job of showing Ms. Sloane’s life through phases of grief (and seeming professional oblivion) to rebirth and new beginnings. Often, these new beginnings would come just in the nick of time as Ms. Sloane was contemplating quitting or finding a new line of work. How do you think this film, which was released not long after her death, fits into her story of ups and downs, despair to ascendancy?

She certainly had many ups and downs. And I had to find a rhythm for that in the edit, because I didn’t want the audience to grow tired from repetition, but we also needed to experience her many wins and losses greatly enough to really empathize with her situation. As far as how this film fits into that piece of her life, I’m hoping this project can be seen as one final triumph, one final rebirth after so much self doubt and years of grief.

Filmmaker Bonus: Do you remember the last conversation you had with Ms. Sloane? What did you speak about? And she get to see an early version of the film?

This is a tough one, because at the very end, she could barely finish sentences after her stroke. And she was just so frustrated with her situation physically. But before the stroke, I remember one of our last really great conversations. Surprisingly, she said she was happy to be done with singing, at least for the time being. She felt she’d accomplished her major bucket list item. And she talked about how she was keeping busy during Covid by baking cakes, bashing Trump, and envisioning a time when we’d finally reached the end of Covid, when perhaps we’d all dance in the streets and there’d be a renewed appreciation for jazz and the performing arts.

To answer the second part of the question, yes, she did get to see a very nearly finished version. Our producer and longtime friend to Carol, Stephen Barefoot, would show her edits when he’d visit her at the senior home in Boston. Upon seeing the last one, she had some notes, mostly on how she looked like an old lady, but she turned to Stephen after it was over and said, “Thank you for telling the truth.” She had longed for her story to be told, and despite her troubles at the end, I don’t think she ever stopped dreaming that it would make its way out there somehow. And to have her blessing meant more to me than I can explain. She was an incredible woman who made a lasting impression on me, and I just hope people will walk away from this film feeling a little more enlightened having spent 90 minutes with Sloane.